SLAP Tears in 2025. What Really Matters?

Oct 27, 2025

It started, as many surgical revolutions do, with a few clever surgeons with keen eyes in the 1980s.

What they found in this case looked dramatic, a tear in the cartilage rim of the shoulder socket (glenoid), right where the long head of biceps tendon originates from.

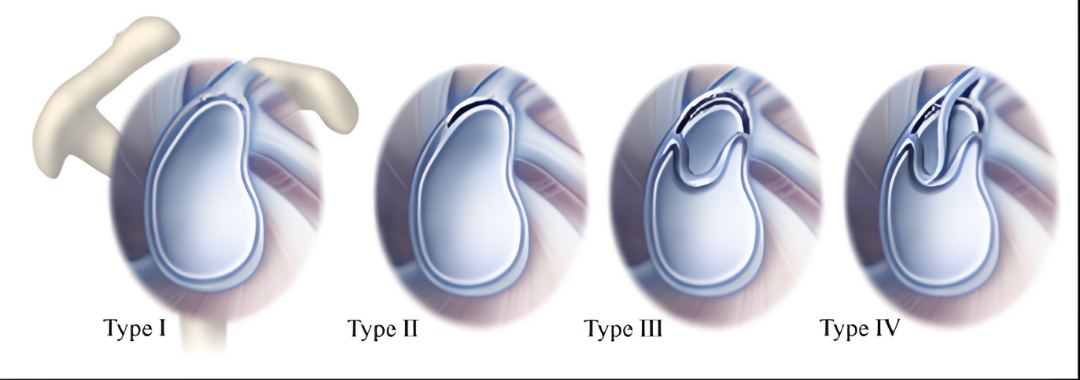

In 1985, James Andrews and colleagues described these tears in throwers (1). Five years later, Stephen Snyder gave them a name that would echo through the next three decades of shoulder surgery: the SLAP lesion: Superior Labrum, Anterior to Posterior tear. He even gave it a tidy four-part classification system (Figure 1) that is still used across the world today (in some shape or form).

And that’s when the trouble began.

From discovery to dogma

What began as an interesting finding quickly became a diagnosis and an explanation for an individual’s shoulder pain.

Then, as imaging improved, it became an epidemic.

By the late 1990s, MR arthrograms were lighting up “labral abnormalities” in throwers, labourers, and weekend athletes alike. Many of these people had pain; some didn’t. But the images looked convincing, and surgical repair felt decisive, conclusive. A new era of shoulder intervention was underway.

The assumption was: if the labrum is torn, it must be the cause of pain, and fixing it should make people better.

How does a SLAP tear happen?

The peel-back mechanism, described by Burkhart and Morgan (2), offered an elegant explanation.

In the late cocking phase of throwing, that split second before a pitcher unleashes a fastball, the biceps tendon shifts its pull posteriorly, twisting against the labrum and literally peeling it off the glenoid rim like tape.

It’s a beautiful piece of biomechanics, and it gave SLAP tears a plausible, even inevitable, narrative in throwing athletes.

Every throw became a small act of self-damage. A slow, torsional undoing of the shoulder’s soft-tissue architecture.

But beautiful stories in medicine are often seductively false or oversimplified.

When ‘tears’ don’t hurt

In 2005, imaging studies of professional handball players revealed that 93% of dominant shoulders showed labral abnormalities (3). Yet only a third of those players had pain.

A decade later, MRI studies in healthy, middle-aged adults found over half had “SLAP tears” despite being completely symptom-free (4).

The message was becoming clear: labral changes are common, often incidental, and poorly correlated with pain.

Our eyes were seeing more than our understanding could explain.

SLAP surgery meets its placebo

For years, a common response to a diagnosed SLAP lesion was surgical repair. Type I and III lesions were cleaned up; Type II and IV were stitched back down.

But as data accumulated, outcomes proved inconsistent, particularly in older athletes and throwers.

Then came a decisive study in 2017 (5).

A randomized trial compared labral repair, biceps tenodesis, and sham surgery.

All groups improved. None were statistically superior.

The conclusion: it wasn’t clear that surgery was doing the healing.

Rehabilitation takes centre stage

Recent research offers some optimism for non-surgical management, but the results are mixed.

A 2022 review found that around half of athletes with SLAP tears returned to sport after rehabilitation, and that success rates improved, to roughly three in four, among those who actually completed the program (6). That’s encouraging, but far from definitive.

Most published rehabilitation programs are generic and outdated, often focused on early motor control, stretching supposed tight structures, and restoration of range of motion deficits. Rarely, did programs include a simple return-to-throwing program to supplement their rehab. Few studies describe the content or quality of the rehab itself, and almost none evaluate how modern, sport-specific loading might alter outcomes.

In short, non-surgical rehab isn’t a panacea. It works for some, fails for others, and is rarely implemented with the sophistication that contemporary athletes deserve.

Rethinking the lesion

After four decades of research, SLAP tears are no longer a mystery.

They’re a mirror.

They reflect how quickly medicine can move from observation to certainty, and how easily structure can be mistaken for cause.

The labrum, once seen as the source of pain, is now better understood as one piece of a complex shoulder system, capable of change, adaptation, and resolution without stitches.

The takeaway

SLAP tears are real.

But they are not always relevant.

Imaging shows us morphology, not meaning.

Surgery can repair tissue, but not always restore confidence, coordination, or load tolerance.

Non-surgical rehabilitation is also imperfect, and we need to update our archaic understanding of what good rehab means for individuals with SLAP tears.

References

- Andrews JR, Carson WG, Jr., McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337–41.

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD. The peel-back mechanism: its role in producing and extending posterior type II SLAP lesions and its effect on SLAP repair rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):637–40.

- Jost B, Zumstein M, Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M, Gerber C. MRI findings in throwing shoulders: abnormalities in professional handball players. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005(434):130–7.

- Schwartzberg R, Reuss BL, Burkhart BG, Butterfield M, Wu JY, McLean KW. High Prevalence of Superior Labral Tears Diagnosed by MRI in Middle-Aged Patients With Asymptomatic Shoulders. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(1):2325967115623212.

- Schroder CP, Skare O, Reikeras O, Mowinckel P, Brox JI. Sham surgery versus labral repair or biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder: a three-armed randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(24):1759–66.

- Steinmetz RG, Guth JJ, Matava MJ, Brophy RH, Smith MV. Return to play following nonsurgical management of superior labrum anterior-posterior tears: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(6):1323–33.

The Complete Clinician

Tired of continuing education that treats clinicians like children who can’t think for themselves?

The Complete Clinician was built for those who want more.

It’s not another lecture library, it’s a problem-solving community for MSK professionals who want to reason better, think deeper, and translate evidence into practice.

Weekly research reviews, monthly PhD-level lectures, daily discussion, and structured learning modules to sharpen your clinical edge.

Join the clinicians who refuse to be average.