Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for shoulder pain: science or science fiction?

Jul 27, 2022

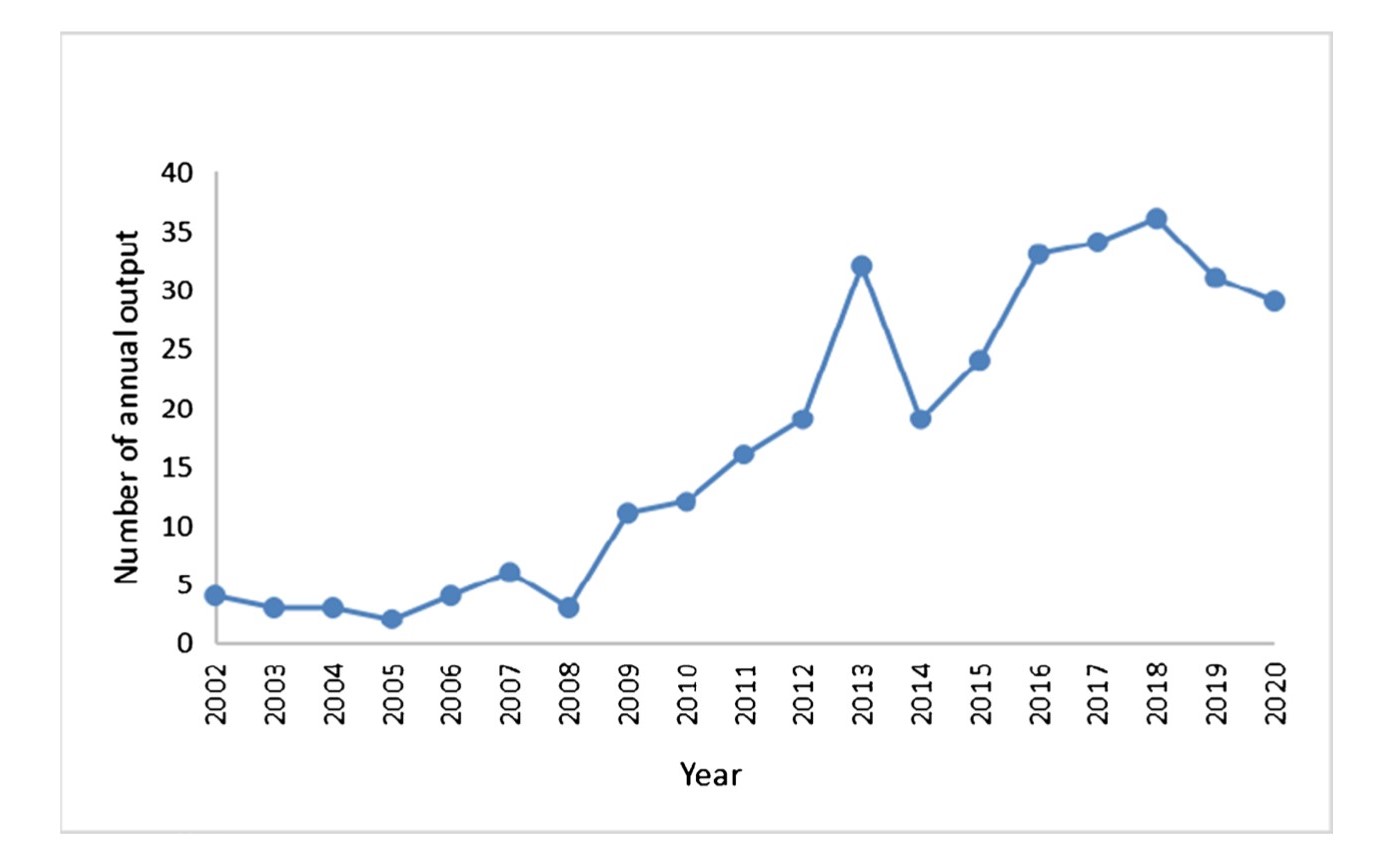

Recently, for some inexplicable reason, I have experienced a significant uptake in patients asking me about platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for their shoulder pain. Perhaps this is a case of selection bias given I tend to see patients with more persistent shoulder complaints and they're often willing to try absolutely anything that could, in principle, reduce their pain (I completely understand). There is evidence too that suggests PRP is still a hot area of research and perhaps this is translating into greater awareness from the general public (ref) (Figure 1). Okay, so maybe it is somewhat explicable. So, what’s the story with PRP in relation to shoulder pain?

Fig. 1 The annual number of publications on PRP in orthopaedics between 2002 and 2020 (ref)

Proposed mechanism of action

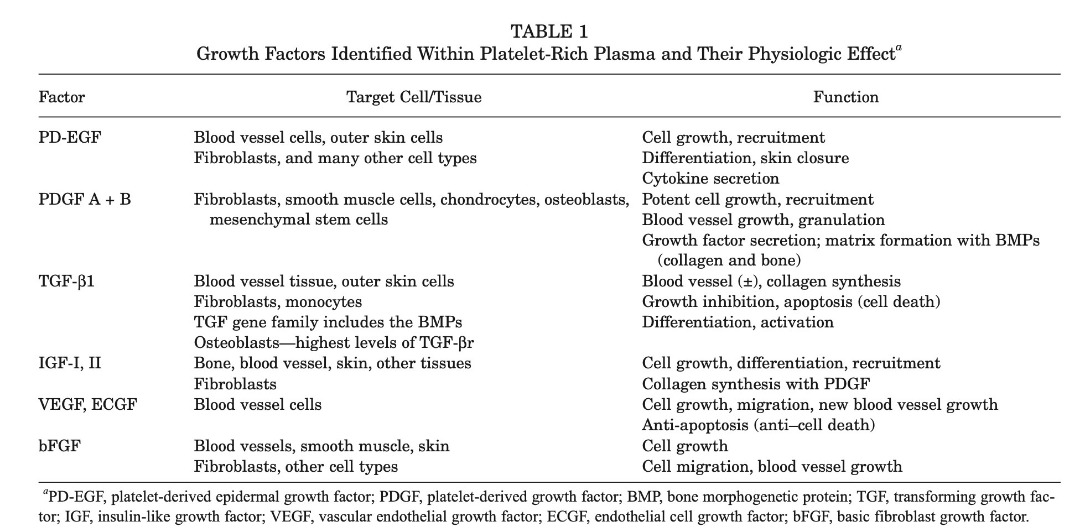

It’s all about that healing. PRP is part of the ‘new wave’ of regenerative medicine. Joe Rogan probably has an episode on it. PRP apparently houses a veritable who’s who of chemical agents involved in the healing process and can even cure male pattern baldness! (It doesn’t but we’re led to believe it does). See table 1 below for a list of the ‘bioactive’ growth factors that are found in PRP, it’s actually quite impressive. Who wouldn’t want his cocktail of goodness injected into their sore spot?! So, the basic science and method is as follows:

Step 1: draw blood

Step 2: spin it around in the spinney thing (centrifugation) to isolate platelet-rich plasma

Step 3: inject it into the site where the miracle is to take place (for the shoulder, typically, it is the subacromial space rather than the tendon itself. Why? Because all that matters in the shoulder is in the subacromial space, right?!

Step 4: watch the magic happen

Table 1

Is it really this simple? Actually, no. Some believe that the true effect of PRP comes from its anti-inflammatory mechanism and has nothing to do with its proposed anabolic/healing effect (ref). There is also active discussion about the best method and dose of PRP administration (see later). Like anything in health science, PRP is plagued by controversies, paradoxes and limited research. Remember evidence based medicine is very young , this should not be surprising (ref).

Is the proposed healing mechanism biologically plausible?

Maybe. It’s intuitive to want to bathe ‘damaged tissue’ in a sea of growth factors and hope this will translate into improved tissue (often tendon) health and thus less pain. But is pain really as simple as enhancing tissue structure? (rhetorical question). Does PRP do what it claims; enhance tissue structure? Honestly, the evidence base is small and inconclusive. There is no definitive evidence that suggests PRP improves the healing of rotator cuff tissue relative to another injection type (or even exercise) in human subjects (ref). This fabulous study by Schwitzguebel et al 2019 in The American Journal of Sports Medicine compared PRP to saline in its ability to positively influence rotator cuff tear healing, shoulder pain and function in people with rotator cuff tears. The results of this study don’t make happy reading for PRP proponents: there were no differences in rotator cuff tear size, pain and function between PRP and saline injections but there were more adverse events in the PRP group. There are some laboratory studies (in rats, mostly) that show it might be effective for stimulating healing (ref) but nothing much in humans. So, the ‘healing’ propaganda of the PRP marketing companies has probably been a touch ambitious, given the current evidence (note: I don’t hate big pharma!).

What about good old efficacy and effectiveness?

Efficacy first. How does PRP compare to placebo for managing shoulder complaints? PRP might (just might) be slightly better than a placebo injection in the medium term only for managing rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP) according to very flimsy evidence from a few clinical trials (ref). There was no difference at short (<8 weeks) and long term (>1 year) follow-ups. For me, this means the efficacy is still uncertain.

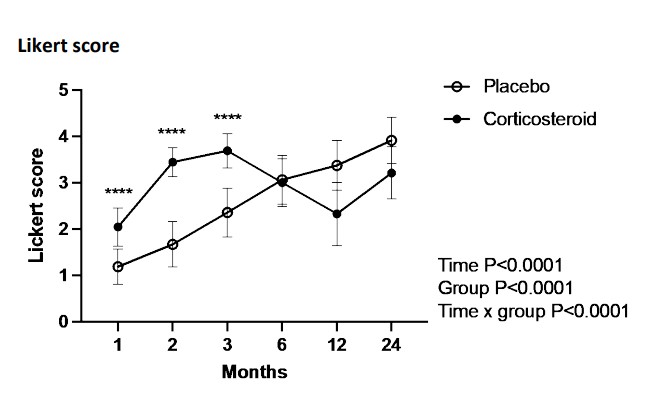

What about effectiveness? Compared to a corticosteroid injection (CSI), PRP is worse at short-term follow-ups and then similar at longer-term follow-ups (ref). Given this, I would probably rather people receive a PRP injection instead of a CSI because of the uncertain and possible toxic effects of corticosteroids. Remember, CSI almost always outperforms comparator interventions in the short term but tends to worsen over time. We’ve seen this numerous times with tennis elbow research (ref) and the graphs tend to mimic figure 2 below. A dramatic short-term improvement in the CSI group followed by steady regression.

Figure 2

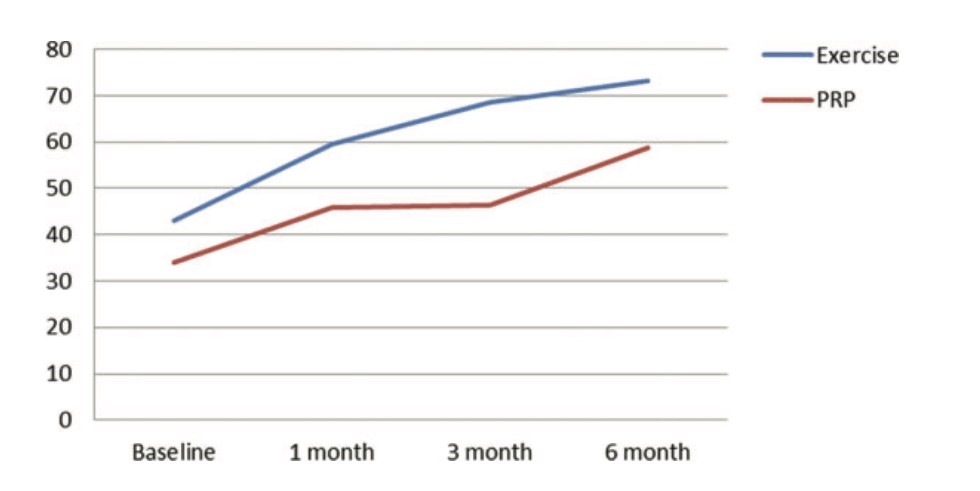

What about exercise? I could only find one rigorous clinical trial investigating this and it is by Nejati et al 2017. This trial compared a PRP alone group Vs an exercise alone group and followed up participants at 1, 3, and 6 months. The results were that exercise was superior to PRP, up to 3 months, for pain and function and there were no major differences in ROM and rotator cuff structure. This does tickle my biases but this trial should be replicated before we get too carried away. See figure 3 below for a nice graph of functional outcomes:

Figure 3. Comparison of total Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC) between the 2 groups, PRP, platelet-rich plasma.

Methodological issues

Some PRP advocates, quite rightly, proclaim the evidence base is flawed due to differing PRP administration techniques/methods in clinical research (ref). This renders interpretation of PRP research challenging and suggests there is far more work to be conducted in this area. We see similar problems with exercise research, where exercise programs are often poorly reported, making it hard to interpret and replicate this research (ref). I would like to see another 5-10 really good clinical trials with open and transparent methods comparing PRP with placebo (saline) injection, CSI, and simple progressive exercise.

Concluding thoughts

PRP doesn’t appear to be a panacea for RCRSP. It might not outperform saline injections and based on a VERY narrow evidence base (1 trial) is probably worse/equivocal compared to exercise alone. It could be an option for those who have tried gallantly with exercise-based rehab and are failing to progress after several months (ref). The risks are probably low, but not zero, and the benefits are probably negligible versus simple exercise. What I say to my patients who ask about PRP: “you can certainly try PRP and you are within your rights to do so, there is no strong scientific evidence/consensus/basis for me to recommend this for you based on the evidence at the time of speaking. I am happy to provide some resources for you to read and you can come to your own decision, or, you are more than welcome to consult a sports physician or orthopaedic surgeon who might specialise in this area”. PRP seems to be just another thing in MSK medicine that is pretty similar to all the other things. It doesn’t deserve the media hype but I think continued research is warranted, in light of the aforementioned limitations of current evidence. As it stands, there is NO strong scientific evidence to support the routine use or recommendation of PRP in clinical practice for the management of RCRSP. Until this changes, I remain sceptical.

The Complete Clinician

Tired of continuing education that treats clinicians like children who can’t think for themselves?

The Complete Clinician was built for those who want more.

It’s not another lecture library, it’s a problem-solving community for MSK professionals who want to reason better, think deeper, and translate evidence into practice.

Weekly research reviews, monthly PhD-level lectures, daily discussion, and structured learning modules to sharpen your clinical edge.

Join the clinicians who refuse to be average.